Clinical Profile and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Neovascular Glaucoma in a Tertiary Hospital in the Philippines

Angela Therese Y. Uy, MD, John Mark S. de Leon, MD, Jubaida M. Aquino, MD

Department of Health Eye Center, East Avenue Medical Center, Quezon City

Correspondence: Angela Therese Y. Uy, MD

Unit 38C Tower 2 Robinsons Place Residences, Padre Faura, Ermita Manila, 1000

e-mail: angela.therese.uy@gmail.com

Disclaimer: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Neovascular glaucoma (NVG) is a blinding disease characterized by intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation and anterior chamber neovascularization.1,2 In Asian population-based studies, NVG accounts for 0.7-5.1% of all glaucomas.3,4 Locally, there is limited available data. NVG was a common secondary glaucoma in the two local clinic-based retrospective studies, accounting for 7.4 and 4.8% of all glaucomas in a private and a government hospital, respectively.5,6 In another local study, NVG was more frequently observed in government hospitals versus private hospitals: 73.8 versus 26.2%, respectively.7 These studies did not include detailed demographics, clinical characteristics, and responses to treatment which could help drive local health policies. The objective of our study was to describe demographic profiles, clinical characteristics, and treatment outcomes of NVG in a tertiary public eye center.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted at an eye center of a tertiary, urban, government hospital. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the East Avenue Medical Center and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Medical charts of patients diagnosed with NVG from January 2000 to August 2018 were retrieved and reviewed. Demographic data (sex, age), risk factors, clinical characteristics including presenting symptoms, NVG stage, baseline and final IOPs and visual acuities (VA), initial glaucoma medications, and lens status were collected. Description of the management and statistical analysis were done on patients who underwent at least one of the following procedures and who had at least one month of follow-up after the procedure: intravitreal bevacizumab injection (IVBe), pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP), trabeculectomy with mitomycin C (trab-MMC), and/or diode laser cyclophotocoagulation (DLCP). Primary outcome measures were VA in the LogMAR scale and IOP. Patients who underwent phacoemulsification during the follow up period were excluded from the study. The treatment outcomes of patients who did not undergo any procedure were not analyzed.

Data collected from the patients’ charts were encoded in Microsoft Excel Spreadsheets. SPSS version 25.0 statistical software (IBM Corporation, New York, USA) was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, median, mean, and standard deviation) were used to describe the baseline characteristics of patients.

Wilcoxon test was used to compare the primary outcome measures at baseline and last clinic visit. One way z-test of proportion was used to compare the VA conversion to NLP. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare variables such as patients with and without IVBe injection and diabetic retinopathy (DR) versus CRVO. Kruskall Wallis test was used to compare patients with 1 to 3 procedures: IVBe versus DLCP versus trab-MMC. Hypothesis tests were accepted at a significance level of less than 0.05 (p<0.05).

RESULTS

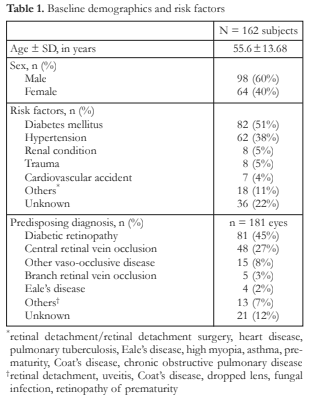

This study included 181 eyes of 162 patients diagnosed with NVG. Baseline demographics and risk factors are listed in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 55.6 ± 14 years and majority (60%) were males. Most patients were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (51%) and hypertension (38%). Diabetic retinopathy and central retinal vein occlusion were observed in 81 (45%) eyes and in 48 (27%) eyes, respectively (Table 1).

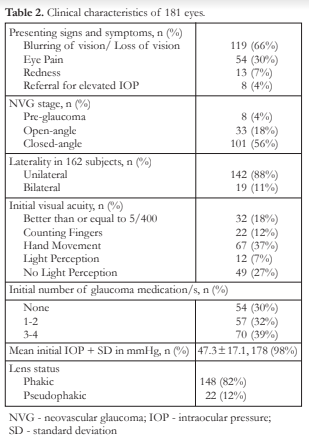

Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of the patients. Most patients (n=119 or 66%) presented with blurring of vision or loss of vision. Eye pain was observed in 54 (30%). Baseline VA of hand movement was observed in 67 (37%) eyes and no light perception (NLP) was observed in 49 (27%) eyes (Table 2). Most of the eyes (n=101 or 56%) were in the closed angle stage of NVG and were phakic (n=148 or 82%). Unilateral involvement was observed in 142 (88%) eyes (Table 2). Majority (n=10 or 52%) of patients with bilateral eye involvement had diabetic retinopathy

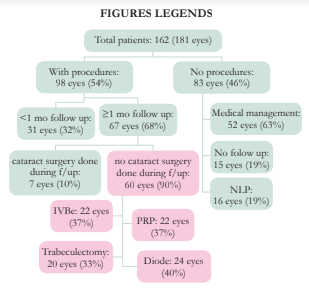

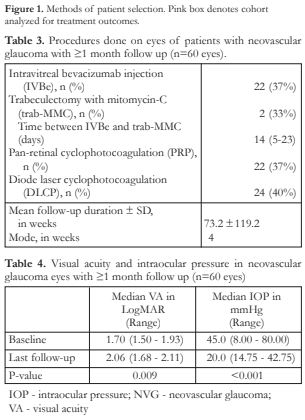

Ninety-eight (98) eyes underwent at least one procedure and the average number of procedures done was 1.5 ± 0.7 per eye. Among eyes that received procedures, only 60/98 (61%) had at least 1 month of follow-up and did not undergo cataract surgery (Figure 1). The mean length of follow-up after a non-medical intervention was 73 ± 119.1 weeks. In this group, IOP decreased from baseline of 45 to 20 mmHg (p=0.000) but VA declined from 1.70 to 2.06 LogMAR (p=0.009) (Table 4).

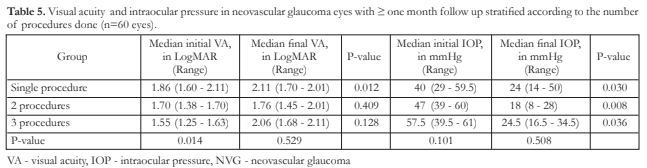

There was a significant decline in VA of those eyes that underwent only one procedure (DLCP only, trab-MMC only, IVBe only) [p=0.012]. There was no significant decline in VA of those eyes that underwent 2 procedures (combination of IVBe with DLCP or IVBe with trab-MMC) and 3 procedures (combination of IVBe, trab-MMC and PRP, and DLCP, IVBe and PRP) [p=0.409 and p=0.128, respectively). Reductions in IOP in the 3 groups from their respective baselines were significant (p<0.05) (Table 5).

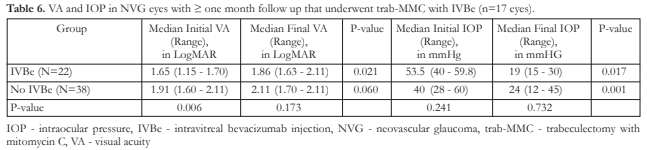

In eyes that underwent trab-MMC, there was significant decrease in VA for IVBe group and significant IOP drop for both the IVBe group and the no IVBe group (Table 6).

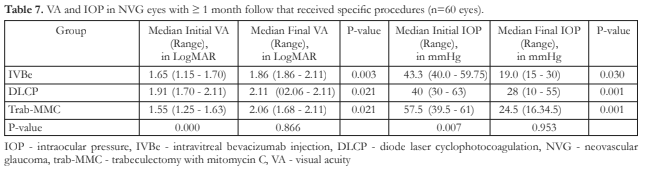

When comparing IVBe, trab-MMC and DLCP, VA significantly declined for each group but with significant IOP control (Table 7). Hyphema and choroidal effusion were among the complications noted after undergoing the procedures.

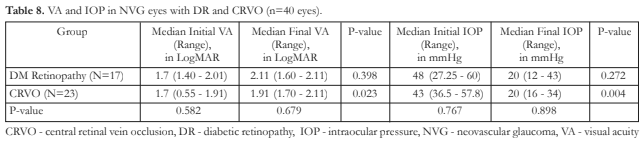

In a subgroup analysis, eyes with CRVO, unlike eyes with DR, revealed a significant decline in VA and significant decrease in IOP after procedures done (Table 8).

Of the 132 eyes who had at least some vision at baseline, 49 eyes had at least one month follow up and underwent at least one procedure. Of these 49 eyes, 19 eyes (39%) converted to NLP (p<0.01). Among those eyes that received procedures and had at least one month of follow up, regardless of baseline vision, 20 (33%) eyes of patients retained or improved VA and 29 (48%) eyes had worsened VA or converted to NLP.

DISCUSSION

The demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients with NVG in this study were similar to other published studies. In Mexico, China and Saudi Arabia, most NVG patients were male, phakic, unilateral, with DR and CRVO/hypertension as the most frequent predisposing conditions.1,8,9 Most of the eyes of the patients with NVG in our study presented in the late stage of the disease with poor VA, high IOP, and closed-angle glaucoma similar to the other studies.1,8,9 Thus, many eyes in our study required end-stage procedures such as DLCP, and consequently these eyes were not able to receive the definitive treatment for retinal ischemia such as PRP and IVBe.

We purposely excluded patients who had less than one month of follow-up after the procedure or who had cataract surgery during the procedures or within the follow-up duration so as to remove confounding factors that may influence the last visit VA. Subjecting our NVG patients to procedures (IVBe, PRP, trab MMC, and DLCP) may have significantly lowered IOP. However, VA significantly worsened in about 1 year average follow-up time. Although not included in the analysis, the progression and complications of concomitant retinal vascular disease due to poor control of co-morbidities (i.e., diabetes mellitus and hypertension) could have resulted to continuous loss of vision. An interesting observation in the subgroup analysis was the significant decline in VA if only a single procedure was done compared to multiple procedures, where the VA change was not significant. IOP, however, whether single or multiple procedures, was significantly lower for both. One reason for this observation could be that those eyes that underwent two or three procedures had already very poor baseline vision and had reached a “floor effect” (the baseline VA for each of the groups depending on the number of procedures done were significantly different, p = 0.014).

The addition of IVBe to trab-MMC in our study failed to show any statistical difference in terms of IOP and VA. There was an average of 14 days of IVBe injection prior to trab-MMC which theoretically could improve bleb morphology but has not been proven to lower IOP. A systematic review by Simha et al. found that there is no evidence to evaluate statistically the effectiveness of anti-VEGF treatments, even as an adjunct to conventional treatment in reducing the IOP in NVG.10 Similar findings of no difference were observed in another study where they compared DLCP alone or with IVBe, and trabeculectomy alone or with IVBe, respectively.11

Interpretation of results is limited by the retrospective study design and short duration of follow-up and significant drop-out rate. Almost half (46%) of all the eyes did not receive any procedure due to the high drop-out rate. Advanced NVG eyes with serviceable vision definitely need aggressive management more than just topical or oral glaucoma medications to preserve vision. Sixty-three percent (63%) of those who dropped out just received glaucoma medications. Nineteen percent (19%) of those who dropped out had NLP in the NVG eye. It was also noteworthy that in our cohort of NVG patients who had some vision at baseline and underwent at least one procedure with follow-up for at least one month or more, 39% of all the eyes converted to NLP.

Our study also was limited by lack of a standard protocol for managing this disease and the small number of patients who underwent specific procedures which limited our analyses. The outcome parameters (IOP and VA) were not matched at baseline to adequately assess the response to the specific procedure. Furthermore, the treatment out comes were not analyzed according to the stage of the disease. A prospective study would better assess the efficacy of the specific procedures and would better address the above limitations.

Since prevention is recommended by most studies to approach NVG, a prospective cohort study involving high-risk groups such as patients with DR and hypertension would be worth investigating, correlating risk factors such as glycemic and hypertension control and instituting treatment at an early phase.

In conclusion, NVG seen in our tertiary center usually presented late with advanced NVG and poor VA. Most of the patients had DR and CRVO. Better IOP control was achieved with combinations of IVBe, DLCP, trab-MMC, and PRP. However, a great percentage of eyes still lost vision despite aggressive measures. Aggressive screening for NVG among high-risk groups such as patients with DR and hypertension/CRVO is warranted to institute treatment at an early phase to prevent vision loss.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank Angelica Fabillar, Philippine-based market research analyst at Euro monitor International (Singapore), for providing expert support with respect to statistical analysis and interpretation of the relevant study data.

REFERENCES

- Al-Bahlal A, Khandekar R, Al Rubaie K, et al. Changing epidemiology of neovascular glaucoma from 2002 to 2012 at King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, Saudi Arabia. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65(10):969-973.

- Barac IR, Pop MD, Gheorghe AI, et al. Neovascular secondary glaucoma, etiology and pathogenesis. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2015;59(1):24-28.

- Wong TY, Chong EW, Wong WL, et al. Prevalence and causes of low vision and blindness in an urban Malay population: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(8):1091-9.

- Narayanaswamy A, Baskaran M, Zheng Y, et al. The prevalence and types of glaucoma in an urban Indian population: the Singapore Indian Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(7):4621-7.

- Martinez J, Hosaka MB. Clinical profile and demographics of glaucoma patients managed in a philippine tertiary hospital. Philipp J Ophthalmol. 2015;40:81-87.

- FlorCruz NV, Joaquin-Quino R, Silva PA, et al. Profile of glaucoma cases seen at a tertiary referral hospital. Philipp J Ophthalmol. 2005;30(4):161-5.

- Leuenberger EF, Gomez JP, Ang RT, et al. Comparison of the Clinical Profile of Patients with Glaucoma Between Private and Government Clinics in the Philippines. Philipp J Ophthalmol. 2019;44:45-53.

- Lazcano-Gomez G, Soohoo JR, Lynch A, et al. Neovascular glaucoma: a retrospective review from a tertiary eye care center in Mexico. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2017;11(2):48-51.

- Liao N, Li C, Jiang H, et al. Neovascular glaucoma: a retrospective review from a tertiary center in China. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16(1):14.

- Simha A, Braganza A, Abraham L, et al. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10(10):CD007920.

- Fong AW, Lee GA, O’Rourke P, et al. Management of neovascular glaucoma with transscleral cyclophotocoagulation with diode laser alone versus combination transscleral cyclophotocoagulation with diode laser and intravitreal bevacizumab. J Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;39(4):318-23.